Texts: Isaiah 7:10-16 • Psalm 80:1-7, 17-19 • Romans 1:1-7 • Matthew 1:18-25

To all God’s beloved children, who are called to be saints;

Grace to you and peace from God our Parent and our brother, Jesus Christ. Amen.

In my newsletter article earlier this month I mentioned how when I was in grade school I used to keep the JC Penny’s catalogue that arrived at our house this time of year, paging covetously through the toy section, making lists of things I wanted for Christmas. In particular I went straight to the Star Wars action figures and would stare at those pages for what seemed like hours – just wishing, hoping, that I could have them all. These days my parents and sister have to pester me for weeks to give them ideas for Christmas gifts – but not back then.

When I was in fifth grade my parents began talking to me about adoption. Specifically, they began talking with me about the possibility that I would be gaining a brother or sister through adoption. As I recall, I was fairly enthusiastic about the idea. Somehow it seemed very like the Christmas catalog method of shopping. You select an agency, you tell them what kind of child you’re looking for, and then you wait for it to be delivered.

I wanted a brother. My parents told me I was getting a sister. That seemed unfortunate, but I supposed I would get used to it. Somehow the fact that she was coming from another country made up for the fact that she had to be a girl. I’d never really heard about Thailand, but my parents explained it was just another name for Siam, the country from the musical “The King and I.” I thought about Yul Brynner and Deborah Kerr, and all the good songs from that show; “I Whistle a Happy Tune” and “Getting to Know You” – which seemed very appropriate for a sister gained by adoption – and I thought it might be alright.

It has been for me, and for my sister Tara, for our family, very alright. Not easy – but quite alright. I remember the first time I saw her in real life, not in one of the photographs the agency gave us to look at while we waiting, but actually her. We were in a taxi, pulling into the adoption agency’s office in Bangkok, Thailand and there was a woman standing at the gate with two small children on either side holding her hands. My sister was one of them. I recognized her immediately. I felt a huge rush of excitement and love for this total stranger who I was about to meet in the flesh. Something in me deeper than biology bonded with her in that instant and she has been precious to me ever since.

Biology is the matter at hand in the readings for this morning. Isaiah provides a vision of a child named Immanuel, and the apostle Paul says of Jesus that he is the one who was promised by the prophets – a descendent of David – a branch of the family tree of Jesse – a Son of God. The stories talk about babies and bloodlines. Biology.

Then comes the gospel.

“Now the birth of Jesus the Messiah took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been engaged to Joseph, but before they lived together, she was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit. Her husband Joseph, being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, planned to dismiss her quietly…” (Mt. 1:18-19)

The pastors in my bible study laughed when we read this together earlier this week. You would think a story that begins by promising to tell how a birth took place might actually discuss the birth. Instead it focuses on a paternity scandal. All that’s said of the birth is, “[he] had no marital relations with her until she had borne him a son; and he named him Jesus.” Sounds like an easy delivery. We decided this gospel was clearly written by a man.

It’s easy to be glib about this story, but it shows us something about how we think about biology, and bloodlines and babies. Where the gospel of Luke, which we were reading last year, begins the story with the story of Elizabeth’s miraculous pregnancy and gives us the beautiful texts of the magnificat and the nunc dimittis, the songs of Mary and Simeon, Matthew’s gospel begins as such, “An account of the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham…”

Matthew, considered to be the most Jewish of the four gospels, pays careful attention to the matter of lineage – because it was assumed that the messiah would come from the lineage of King David, the eternal champion of Israel. So Matthew writes,

Abraham was the father of Isaac, and Isaac the father of Jacob, and Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, and Judah the father of Perez and Zerah by Tamar, and Perez the father of Hezron, and Hezran the father of Aram, and Aram the father of Aminadab, and Aminadab the father of Nahshon, and Nahshon the father of Salmon, and Salmon the father of Boaz by Rahab, and Boaz the father of Obed by Ruth, and Obed the father of Jesse, and Jesse the father of King David.

A nice long line of men, passing their inheritance down to one another, except – did you catch it? King David’s father was Jesse, and Jesse’s father was Obed, and Obed was the child of Boaz and Ruth. This story of how Ruth came to bear a son is the focus of the entire short book of Ruth in the Old Testament and it is significant because Ruth was not an Israelite. She was the widowed wife of an Israelite who followed her mother-in-law, Naomi, and left behind her own countrymen out of love for her adopted family. When Ruth bears a child by Boaz, her mother-in-law claims the child and is able to continue her bloodline. A strange hiccup in the story that shows how widows and foreigners and adoptions have always been a part of the family tree.

Matthew goes directly from an extremely long list of the patriarchs of Israel into a story about Joseph, the adoptive father of Jesus. This is an awkward transition, because we learn from the genealogy that Joseph is of the house of David, and then immediately thereafter we learn that Jesus is not Joseph’s biological child. Yet the gospel of Matthew goes to great pains to speak of Jesus as being in the line descending from Abraham through King David. It’s as if someone is trying to cover up an embarrassing incident… or, perhaps, reveal one.

This is actually the case. Discovering that his intended wife is already with child, Joseph has decided to dismiss her quietly. As a woman promised in marriage to him Joseph could have dismissed her publicly. He could have exposed her pregnancy and she could have been stoned to death. But we are told that Joseph was a righteous man, and from his behavior in this incident we infer that righteousness is connected to mercy and compassion.

Like the Joseph of the book of Genesis who made a way for his f

amily in Egypt by interpreting dreams, Mary’s husband Joseph has an encounter with a messenger of God in a dream and his heart is changed. He does not dismiss Mary as he’d planned to, but instead marries her and gives her child a name.

In the ancient near east the act of naming was the first responsibility of a father and was a sign that the father accepted paternity of the child. Joseph names Mary’s son Jesus, which means “God saves,” and in doing so he effectively adopts the child into his household. On a practical level, Joseph saves – he saves Mary and her son from humiliation and disgrace, and possibly death.

You know the saying, “blood runs thicker than water.” It means family comes first. Maybe that’s why adoption is such a difficult thing for some people to imagine, the sense that what it means to be family is to share blood.

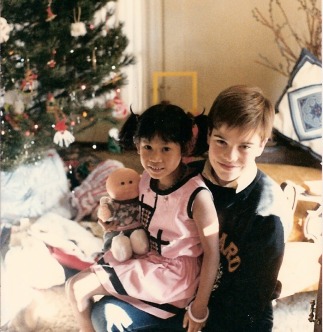

One of the funnier stories my family tells about the months just after Tara came back to the States with us from Thailand touches on this. We didn’t subject Tara to the church people right away, knowing that folks would naturally want to meet her and that it could be overwhelming. When we all did finally go to church my mom and sister were wearing matching pink dresses with black trim we’d brought back from Bangkok. Standing side by side just before worship a pair of well-intentioned church ladies approached them and said to my mother, “well… she has your hair.”

One of the funnier stories my family tells about the months just after Tara came back to the States with us from Thailand touches on this. We didn’t subject Tara to the church people right away, knowing that folks would naturally want to meet her and that it could be overwhelming. When we all did finally go to church my mom and sister were wearing matching pink dresses with black trim we’d brought back from Bangkok. Standing side by side just before worship a pair of well-intentioned church ladies approached them and said to my mother, “well… she has your hair.”

But it goes deeper than that. A while ago, Tara, who is now thirty-two asked me if I think I look more like Mom or Dad. She is very aware that she has no handy reference point against which to compare herself like I do. In a world that says blood is thicker than water, accepting the validity and the permanence of adoption is not easy to do – even twenty-five years later.

On the surface today’s readings are about biology, about blood. But underneath they are about adoption. Consider that without Joseph’s act of adoption the new life begun in Mary through God’s creative power might never have entered the world. The hiddenness of God is how we describe God’s knack for being concealed in the least likely of places – an illegitimate child, a working class carpenter, a crucified teacher. God hides inside the fragility of life and calls us all around to care for and protect the fragile things of life. To adopt one another’s cares and concerns as our own.

In our life together we take this theology of adoption very seriously. The very initiation rite for Christians turns the notion that blood is thicker than water inside out as we pour the waters of baptism over infants and initiates and then name them, something only family has the right to do, and call them sisters and brothers. Then, in case that’s not enough, we share a common cup – passing it to each other saying, “the blood of Christ poured out for you.” We practice in rituals and with words a new reality where we are bonded by both blood and water, tied tight with thick knots.

This is what Paul means when he says that Jesus is our Lord “through whom we have received grace and apostleship to bring about the obedience of faith among all…including [ourselves] who are called to belong to Jesus Christ.”

We are called to belong. To belong to a single family, a single body. We are claimed and named in our baptism, the act of God’s adoption and we are sent out to adopt the world – which is one very good way of understanding what Jesus means when later in the gospel of Matthew he sends the disciples out to make disciples of all the nations by baptizing them (Mt 28:16-20). It doesn’t mean conquering people and colonizing them with your faith. It means claiming the whole world as people as important to you as your own family.

St. Luke’s, you do this very well. You are a wonderful collection of adoptive parents. Many of you have taken others in this room into your homes. You have raised children not born to you. You have welcomed strangers and orphans into your lives. You have given your name, “St. Luke’s,” to outcasts and wanderers in need of a home and in that way you’ve adopted them and made them your own.

This is not necessarily the natural order of things. This habit of adoption stirs up the given understandings of what it means to be family. That’s good. In fact, that’s what we hope and pray during this season of Advent. We pray that God will stir up the power of the Holy Spirit and extend the already inbreaking, already here, already dawning reign of God. We pray that God will continue to stir up our hearts and minds and imaginations so that we will see the world with new eyes that can only see brothers and sisters, that can only respond to the fragility of life by claiming each child as one of our own. By claiming each other.

May God bless us all with the ministry of adoption, and may we grow into an acceptance of the validity and permanence of our own adoption – all of us – by God our parent.

Amen.